- AsiaOne » Afghan province hopes war can be tourism draw

- AFP » Afghanistan’s Stunning Lakes Thirst For Tourism

- The Times » Asia Article about Tourism in Afghanistan Times British

- CNN Traveller » Built to last

- Jessica Wanke » Letter From Afghanistan

- Economic Times Mumbai » Growing The Tourist Market

- Tourism in Afghanistan

- Afghan province hopes war can be tourism draw

- Unama » Afghanistan Sees Surge in Domestic Tourist Industry

- BBC News » Do tourists really go to Afghanistan?

- Afghan News » Afghan team’s journey to ‘Incredible India’

- Lemonde Dimplomatique » Afghan Tours

- Afghan Dreams » Afghan Dreams

Media Features

AsiaOne » Afghan province hopes war can be tourism draw

AFP

Wed, Jun 01, 2011

By Katherine Haddon

Panjshir, around 130 kilometres (80 miles) northeast of the capital Kabul, is dominated by the snow-capped mountains of the Hindu Kush, plunging valleys and a fast-flowing river which snakes through the middle.

It is also one of Afghanistan’s most peaceful areas. Panjshiris, mainly ethnic Tajiks, pride themselves on having kept out the Taliban and repelled the Soviet Union after its 1979 invasion.

US and Afghan officials hope this history and natural beauty could bring visitors to Panjshir and boost its economy as it makes the transition to Afghan security control from July, amid fears that foreign aid could plunge.

“This is not going to be Afghan Disneyland, this is not going to be Sandals resort Jamaica, this is Panjshir and we need to develop a style of tourism which is unique to Panjshir,” said Morgan Keay, a tourism specialist at USAID, the US government’s aid agency, who is working in the area.

People involved acknowledge there is a long way to go before most foreigners can be persuaded that Panjshir is safe enough for them. “For any clients who contact us, this is the first question – is Afghanistan safe?” said Muqim Jamshady, CEO of Kabul-based travel company Afghan Logistics and Tours. “Of course it’s very hard to convince clients.”

Panjshir was the home of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic French-speaking anti-Taliban commander often credited with forcing out the Soviets but who was assassinated two days before the September 11, 2001 attacks.

His tomb in the province – surrounded by abandoned, rusting Soviet tanks and trucks – is being developed into a $10 million tourist attraction complete with mosque, library and conference centre.

Officials expect Massoud’s legacy to act as a focal point for tourism, along with adventure activities such as mountain trekking and kayaking. Mohammad Sorab Marazi, an ex-mujahedeen fighter who is now governor of the province’s Dara district, said: “As Panjshir is one of the resistance centres against the Soviets and Al-Qaeda, everyone in the world knows about it… that’s why people should come here and see what type of place it is.”

Asked whether he would be happy to see Russian tourists coming to the area to explore historic battlefields, he added: “There will be no problem for the Russians coming to Afghanistan. Let them see the graves.”

However, Panjshir has a long way to go before it develops a tourist industry. It has only two primitive guesthouses, no proper restaurants and certainly no visitor centres.

Some Kabul residents travel to the area for weekend picnics, but virtually no foreign tourists currently come to Panjshir.

Even assuming more people can be persuaded to visit, officials say careful preparations would be needed to ensure that locals are ready for them, perhaps through mullahs.

US officials raised the prospect of local men being offended by the sight of Western men kayaking down the river as women collect water from the banks. Potential investors who spoke at a recent Panjshir tourism conference organised by the US-led Provincial Reconstruction Team also raised practical concerns such as Afghanistan’s lack of long-term leases for hoteliers.

Provincial leaders, though, are hungry for the revenue which tourism could bring.

“Tourists are not coming here to take things from us or insult our religion but to breathe the fresh air in the province,” Abdul Rahman Kabiri, deputy governor of Panjshir, told the conference.

“Tourists will play an important part in the development of this country.” Panjshir will be among the first wave of places in Afghanistan to pass from foreign to local security control from July.

US officials hope that, as their mission here winds down, industries such as tourism can grow enough to help make up for a likely shrinkage of funding from their government and other sources in future.

However, they acknowledge that the success or failure of that idea turns on whether there is peace in Afghanistan after the international troop drawdown, or still more war.

AFP » Afghanistan’s Stunning Lakes Thirst For Tourism

BAND-E-AMIR, Afghanistan (AFP) – During Afghanistan’s 1960s hippy trail heyday, Band-e-Amir’s six mineral-rich lakes and pink cliffs were the country’s holiday paradise, visited by tens of thousands of domestic and foreign tourists every summer. Swan-shaped pedal boats bob in the sapphire-blue lakes of Band-e-Amir as tradesmen peddle their wares on the shore. Then, as if from nowhere, two US Black Hawks roar low over the water. Welcome to tourism Afghan-style, in one of the war-torn country’s few national parks, about 80 kilometres (42 miles) from the town of Bamiyan where the Taliban destroyed the world’s tallest Buddha statues in 2001. “Before the war,” sighed Shah Is’haq, a 68-year-old jewellery salesmen perched on the bank of the placid waters, “thousands of foreigners were coming here. The life, back then, was very good.” “Those days are now gone,” said Is’haq, mourning Afghanistan’s woes from the 1979-89 Soviet occupation, to the ensuing civil war, the 1996-2001 Islamist Taliban regime and now the US-led fight against Taliban insurgents. The roads around the lakes were heavily mined by local militias and the Taliban in the 1990s, and only a dirt track is safe. The journey from Kabul takes a bone-shaking 12 hours, and passes through some areas where attacks have taken place. But the brightly coloured pedalos and trinket sellers at the lakes -dubbed AFG’s Grand Canyon – hint at growing efforts to bring back the golden tourist years despite the violence.

In Bamiyan city, Italian tourist Alessandro Califano said he was aware of the security problems in Afghanistan but had not faced any difficulties himself. “I think it is a wonderful place,” Califano, a museum curator in his native Rome, said at a hotel overlooking the niches in a huge sandstone cliff that once housed the two 1,500-year-old Buddha statues. “Even if the Buddhas have been blown into the air, it has a certain aura. The natural setting is simply fabulous,” he said. “The only threat I faced here was finding a scorpion in the bath,” Califano said, smiling. Otherwise it was “safe and pleasant”. Despite the destruction of the statues in March 2001, officials and residents argue that Bamiyan province can still claw back lucrative tourism. The remains of the statues were declared a UN World Heritage Site in 2003, while the Afghan government has submitted the lakes for recognition on the same list. Bamiyan city opened a rudimentary tourist centre in late October, backed by the New Zealand government which has a small military contingent there, and is now planning a map of key sites and an institute to train hotel workers. “We are working on a project for Bamiyan tourism,” said Habiba Sorabi, the provincial governor and the only woman to hold such a position in Afghanistan. With the population mainly comprising Shi’ite Muslim ethnic Hazaras who loathe the Taliban, Bamiyan is a relative oasis of peace in Afghanistan. This year for example, more than 1,000 “foreigners” visited the scenic valley and Band-e-Amir, the governor said over green tea in her hilltop office. But getting central government funds to pave the bumpy road through green valleys and barren mountains from Kabul is a priority for getting tourists to the area, Sorabi said. “So let’s hope for the future,” she said.

In Kabul, officials share the same hopes but admit that reviving tourism could be tough, with Afghanistan’s infrastructure still in ruins and security suffering from the worsening Taliban insurgency. Nearly 70,000 NATO and US-led troops are still in Afghanistan, and US president-elect Barack Obama has said that he plans to begin pulling US troops out of Iraq to switch the military focus to the Central Asian nation. Under its five-year national development blueprint, the Afghan government says it plans to promote tourism and encourage private investment in the industry. “We have the plans in front of us,” Deputy Information, Culture and Tourism Minister Ghulam Nabi Farhai said in Kabul. “At this time the biggest challenge ahead is security.” He added: “If we have security, if we have good roads & hotels, AFG with its beautiful landscape,its pleasant climate and rich culture and history will become a perfect place for tourists.” Muqeem Jamshedi, the owner of Afghan Logistics and Tours, one of the few tourism firms established in Kabul after the fall of the Taliban, says Bamiyan and the lakes should be on any tourist’s wish-list. “Bamiyan and Band-e-Amir are the must-go places,” said Jamshedi. More than 150 “foreign tourists” have visited the valley this year through his company, which provides transport, hotel and security services, he added. A former journalist, Jamshedi set up the company months after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, with high hopes that tourists would soon flood his country. But so far, he said, his dreams have yet to come true. “Tourists can’t bring security, it’s the security which brings the tourists. I hope for that security,” he said.

The Times » Asia Article about Tourism in Afghanistan Times British

The Times – September 23, 2006

Money changers are keen to offer their services (DOUG MCKINLAY)

YOU HAVE to be nuts to visit Afghanistan as a tourist right now. There’s all-out war in the south, suicide bombers are targeting Kabul, landmines and cluster bombs litter the countryside, and Westerners are hated. True?

Well, somewhat. Certainly it is not the first holiday destination that jumps to mind for most people. There are no beaches, theme parks or casinos, proper hotels are thin on the ground and, in terms of infrastructure, there isn’t a lot. Why go then? Simple. This is an endlessly fascinating country that is living and creating a history like no other place on the planet.

One of the first things to understand is that Afghanistan is a divided country. The southern provinces are definitely a no-go zone. Nato forces are neck-deep in a conflict that seems set to get worse. When this will change is anybody’s guess. However, in the north, things are a bit different. Notwithstanding two recent suicide bombings in Kabul, most of the northern provinces are experiencing relative calm. It’s into this environment that I set out. My goal: to gain an understanding of what Afghanistan is all about and to see what is drawing a small but hardcore group of tourists to this war-torn central Asian country.

First stop Kabul. The city sits in a valley amid dun- coloured hills: a disintegrating medieval perimeter wall can be seen poking between the mud-brick houses that cover them. The noon-time traffic is thick, congested almost to the point of standstill. Kabul’s architecture is a mix of slapped together one-storey buildings, 1970s low-rises and post-Taleban steel and glass structures that look as if they have been lifted from the streets of Shanghai. However, I am on my way to the Serena Hotel, Kabul’s only five-star bolt hole.

Opened in November 2005 after an extensive refurbishment programme, the hotel project is funded by the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) in partnership with the World Bank, Norway’s Norfund and the Netherlands Development Finance Company.

Why open a five-star hotel in one of the most unpredictable cities in the world? “Part of the reason was to help develop the local economy and change the image of Afghanistan,” says Chris Newbury, the Serena’s general manager. “We provide jobs for local people. We train them in the industry and even if they leave us to start their own hotel or guesthouse, hopefully the training they receive here will help improve the country’s overall hotel industry.”

The Serena is not the only project AKDN is involved with in Afghanistan. It is the principal backer of the telecommunications company, Roshan, which provides affordable mobile telephone and internet service to people all over the country. It also provides funding for cultural programmes that are working to restore many of Kabul’s historic buildings and sites, principally the Babur Gardens, the Old Town, and the Timur Shah Mausoleum.

Hotels aside, I want to know more about Kabul itself and the surrounding country; one of the best ways to get a finger on the pulse of any city is to visit the markets.

Kabul is full of markets, most of them unofficial. Any bare patch of ground is suitable for a vendor to sell a few melons or some dates. Walking among these busy streets is like strolling through the pages of National Geographic magazine. Every face is a portrait, every portrait tells a story, every story an epic.

The few Western tourists who make it to Kabul are often warned off from visiting the markets because they’re too unpredictable. Granted, the hustle and bustle might be a bit much for some, but I am treated with nothing more menacing than a little over- curiosity and on a number of occasions even get invited to people’s homes for tea.

Getting around outside the city can be tricky. Independent-minded travellers can do it by public transport, but this is time-consuming and erratic at best, and dangerous at worst. However there are a few private organisations that offer transport and tours around the country. One Kabul-based company is Afghan Logistics. This family-owned business, run by 27- year-old Muqim Jamshady , was more used to acting as fixers for foreign journalists until the first tourists — three people from the UK — turned up in 2003.

“We were very happy,” says Muqim. “Even the Afghan Government was happy. It’s what we want, especially people of my generation. We just want the war to stop. I even hate the word war.” Although Afghan Logistics is not the cheapest (about £53 to £80 a day) for travel, it is among the most knowledgeable and experienced.

CNN Traveller » Built to last

March 2008 Posted in Inside Asia

A charitable foundation led by a former British diplomat is hoping to improve Afghanistan’s prospects through arts and crafts. Kate Brothers reports from Kabul……Click Here to Read More

Jessica Wanke » Letter From Afghanistan

Section: Special Report; Page Number:30

Economic Times Mumbai – Aug 18, 2006

The “pure” tourist has still to make significant numbers But he has started coming. In this interview with Muqim Jamshady, CEO of Afghan Logistics and Tours Pvt Ltd, the potential Indian traveler gets a chance to learn why Afghanistan has always had such a powerful hold on us. It’s the people and the culture and the host of things we have in common.

In the five years your company has been in operation, how long have you been taking tour groups and individuals around?

In 2001 and 2002 Afghanistan was not quite ready for tourism. Therefore we brought our first tour group only in 2003, from the UK. Ever since, each year we have about two or three big parties ranging in size from from 8 to 13 people, overall about 30 to 40 individuals.

How many people have you dealt with so far?

About 140 “pure tourists” since 2003; above and beyond that, many NGO workers, journalists and company workers.>

Is it mostly groups or individuals? Pre-designed packages or customized? For businessman who want a break or for people who come to Afghanistan purely as tourists?

Corresponding with the different customers we have been serving, we have had different requirements. There have been individual and groups traveling, we have provided them with either pre-designed or custom-made packages. Most tourists would take our pre-designed routes, while journalists and the like have more specific and custom-made demands.

In all the time you have operated, have you ever has a mishap in terms of “collateral damage”.

Absolutely NOT. We follow closely the recommendations of ANSO (Afghan National Security Organization) and do not take people to unsafe areas, which mainly constitute the southern provinces. We have not once had a security situation of any type or even a close call of any nature, either.

On a visit to Afghanistan in May 2005, people went out of the way to assure us that Indians were safe. After the murder of the Border Roads engineer K Suryanarayana by Taliban militants in April, does that perception still stand?

The people of Afghanistan respect Indians and the Indian government because of their past support for the anti-Talib resistance. Just like all foreigners are a tentative target of insurgents who are opposed to development, Indians are not more or less exposed. The recent tragic case does not highlight that Indians are specific target and does not reflect the general populations attitude against Indians. In fact, most feel a strong cultural affinity with the subcontinent.

Has the tourism business grown in the last few years?

It has grown each year steadily, but this year because of those protests in Kabul, and some problems in the south which was heavily covered in the Western media, the tourism business has slowed.

Do you think there is a market for Indian tourists? After all, we’re not all that eager to rough it out!

Most of our business at the moment originates from Europe and USA. What we are trying to do is to open up the Asia-Pacific rim (including Australia, New Zealand and South Asia) to tourism in Afghanistan – this is an ongoing marketing effort.

Economic Times Mumbai » Growing The Tourist Market

By Don Duncan / MAZAR-I-SHARIF

TIME.COM – Thursday, Oct. 02, 2008

he lines between the Afghanistan at war and the Afghanistan at peace alter daily. Cities accessible by road today may only be reached by plane — or not at all — tomorrow. And so follow the boundaries of the nation’s tiny tourism industry. The few foreign tourists who come to Afghanistan, estimated to number under a thousand yearly, need plenty of help to pull off their holidays safely. In cities like Kabul, Herat, Faizabad and Mazar-i-Sharif, a small legion of Afghans who spent the last seven years as translators and security aides are spinning their expertise at navigating this shifting landscape into a new business. Now, they are also tour guides.

The young sector is not exactly crowded. Two companies — Afghan Logistics and Tours and — run most of the tours in the country, drawing and redrawing the map — on a daily basis — of where travel is advisable and where it’s not. ”

Blair Kangley, a 56-year-old American, traveled with Afghan Logistics and Tours from Kabul to the Bamian valley, famous as the site of the once-towering Buddhas, blown up by the Taliban in 2001. While tour guide Mobin accompanied Kangley on what was planned to be a two-day tour, he was in continual contact with the head Kabul office, plugged into its own formal and informal information networks ranging from the Afghan army and police to U.S. and NATO intelligence personnel. After word reached Mubim that there was a “block” on what had been the only “safe road” back to Kabul, Kangley found himself hanging out in Bamian for three days more. “We eventually were prepared to take a U.N. flight out,” he says. “The locals unblocked the road just in time and we left by car in an exciting all-night jaunt.”

Indeed, Afghan Logistics and Tours regards itself more as a logistics company than a tourist outfit; tourism comprises only about 10% of its business. “But we hope to increase our tourism to between 60% and 70%,” says Muqim Jamshady, the company’s 28-year-old director who steers security intelligence to his team of driver/guides from his desk in Kabul, littered with over a dozen walkie-talkies and satellite phones. That increase will happen, Jamshady adds, “once Afghanistan gets more peaceful.” He doesn’t speculate exactly when that moment will arrive.

In the meantime, he and Mann continue to organize tours to sites like Bamian and Qala-i-Jangi, a 19th century fortress some 12 miles (20 km) outside Mazar and one of the sites of final resistance by the Taliban against the Northern Alliance and the U.S.-led forces in 2001. Today, the bullet holes along the walls of the fortress remain unplastered. Shoib Najafizada, Afghan Logistics and Tours’ man in Mazar, leads visitors around the rusty remnants of tanks and heavy artillery that lie strewn around. Like other guides, Najafizada offers firsthand accounts of some of the key moments of the country’s recent turbulence. He was present at the battle of Qala-i-Jangi, as a translator for the coalition forces, and today he deciphers the untouched graffiti scratched in Persian and Urdu into black scorched walls of the fortress: “Long Live the Taliban,” or “In Memory of Mullah Mohammad Jan Akhond,” a Pakistani fighter with the Taliban who died in the conflict.

Mann says much of his outfit’s business is in visiting these historic sites of battle. But on some recent tours, he says, “It’s not unusual for a Black Hawk or an Apache helicopter to fly over. And it is clear that [the conflict] I am describing is still going on.” With security as fragile as it is in Afghanistan, there are no real relics there yet. “These battles we describe could be the future as they have been the past.”

(Watch a video about Kabul’s emerging skateboard culture.)

Find this article at:

http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1846464,00.html

Copyright 2008 Time Inc. All rights reserved.

Tourism in Afghanistan

![]()

Trekking through the Pansjir Valley

By Bob Ramsay; Photo Credits: Jean Marmoreo, 29 MAY 2008

Well, maybe. It’s awfully small, with good reason. Aside from the Taliban creating a war zone out of the southern half of a country the size of Manitoba with the population of Canada, there’s the small matter of some bad press.

Despite this (or for aficionados of danger, because of it), tourism is taking the first baby steps to legitimacy in one of the most beautiful and remote locations on earth. In fact, one tour operator has been taking small groups on guided tours for six years, beginning very soon after the Taliban were routed from the north.

Muqin Jamshady is the 30-something owner of Afghan Logistics and Tours, which started as a driving and cab service for the hundreds of UN and NGO staffers and journalists now working in Kabul.

His company is the first government-licensed tour operator to take foreigners on guided tours in the northern part of Afghanistan. They run 6-day, 10-day and 16-day standard tours and will customize any itinerary to suit its participants.

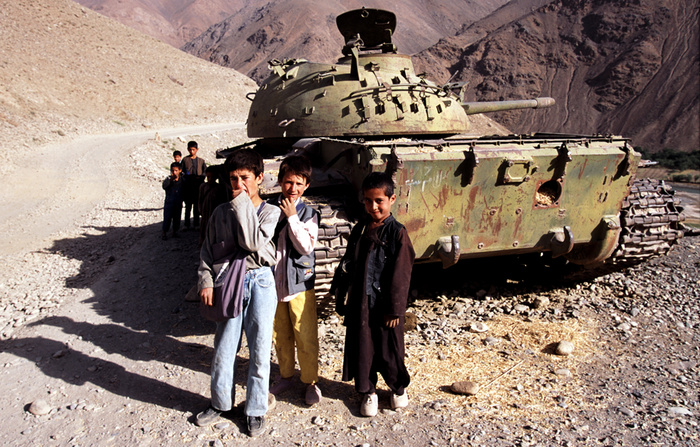

After a few basic security precautions, such as a local cell phone with emergency numbers pre-programmed in, plus a walkie-talkie, plus a GPS emergency-finder, we head out for one of the most beautiful drives on earth, through the Pansjir Valley. It is a two hour trip north of the Afghani capital of Kabul. At the valley’s peak is the breath-taking Anjuman Pass, where Alexander the Great drove his foot soldiers during the terrible winter of 325 BC. Today, the snow-capped mountains plunge steeply into the Pansjir River, with its bucolic woods and lush fields full of poppies and tanks.

Tanks? Yes, tanks. The charred remnants of Russian tanks destroyed by the Mujahadim in the late 70s still dot the landscape, often with grass growing from their turrets. There’s a huge disincentive to move them – the land around them is mined.

But they’re a reminder of just how exotic Afghanistan remains for anyone wanting to go there as a tourist. Then there’s the war against the Taliban, though this is centred in the south of Afghanistan, far from both Kabul and the Pansjir Valley.

All trips start in Kabul, and the easiest way to fly there is through Dubai, either on the government airline, Ariana, or the privately-owned Kam Air.

Muqin Jamshady is very aware that safety is the issue for anyone contemplating a trip to Afghanistan. So he provides armed guards and English-speaking guides on all trips. As he says: “We are always in touch with the local police and relevant security departments, and we always take our own security guards when we go outside of Kabul.”

So how many people last year took one of his tours?

“Seventy to eighty.” Were they happy ?

It seems so, and the upbeat testimonials range from Tony Wheeler, co-founder of Lonely Planet, to any number of hard-bitten media types who have seen it all, all over the world, and swear by him and his colleagues.

Afghan province hopes war can be tourism draw

AFP

Wed, Jun 01, 2011

By Katherine Haddon

BAZARAK, Afghanistan – A HOLIDAY in Afghanistan? It may not sound like an enticing prospect, but one province hopes that its history of warfare can help pull tourists in rather than put them off.

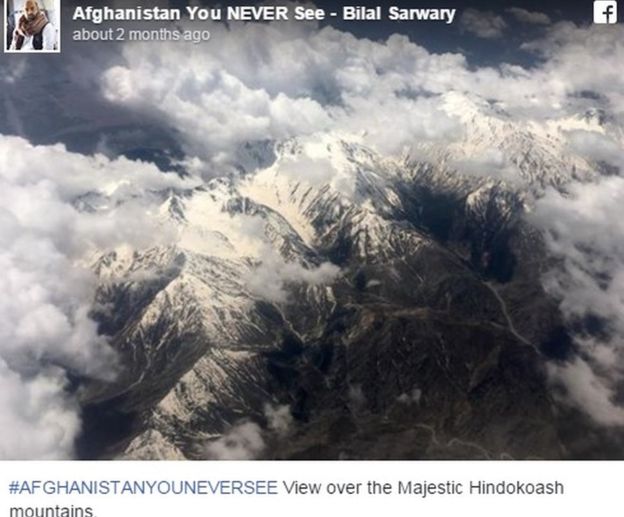

Panjshir, around 130 kilometres (80 miles) northeast of the capital Kabul, is dominated by the snow-capped mountains of the Hindu Kush, plunging valleys and a fast-flowing river which snakes through the middle.

It is also one of Afghanistan’s most peaceful areas. Panjshiris, mainly ethnic Tajiks, pride themselves on having kept out the Taliban and repelled the Soviet Union after its 1979 invasion.

US and Afghan officials hope this history and natural beauty could bring visitors to Panjshir and boost its economy as it makes the transition to Afghan security control from July, amid fears that foreign aid could plunge.

“This is not going to be Afghan Disneyland, this is not going to be Sandals resort Jamaica, this is Panjshir and we need to develop a style of tourism which is unique to Panjshir,” said Morgan Keay, a tourism specialist at USAID, the US government’s aid agency, who is working in the area.

People involved acknowledge there is a long way to go before most foreigners can be persuaded that Panjshir is safe enough for them. “For any clients who contact us, this is the first question – is Afghanistan safe?” said Muqim Jamshady, CEO of Kabul-based travel company Afghan Logistics and Tours. “Of course it’s very hard to convince clients.”

Panjshir was the home of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic French-speaking anti-Taliban commander often credited with forcing out the Soviets but who was assassinated two days before the September 11, 2001 attacks.

His tomb in the province – surrounded by abandoned, rusting Soviet tanks and trucks – is being developed into a $10 million tourist attraction complete with mosque, library and conference centre.

Officials expect Massoud’s legacy to act as a focal point for tourism, along with adventure activities such as mountain trekking and kayaking. Mohammad Sorab Marazi, an ex-mujahedeen fighter who is now governor of the province’s Dara district, said: “As Panjshir is one of the resistance centres against the Soviets and Al-Qaeda, everyone in the world knows about it… that’s why people should come here and see what type of place it is.”

Asked whether he would be happy to see Russian tourists coming to the area to explore historic battlefields, he added: “There will be no problem for the Russians coming to Afghanistan. Let them see the graves.”

However, Panjshir has a long way to go before it develops a tourist industry. It has only two primitive guesthouses, no proper restaurants and certainly no visitor centres.

Some Kabul residents travel to the area for weekend picnics, but virtually no foreign tourists currently come to Panjshir.

Even assuming more people can be persuaded to visit, officials say careful preparations would be needed to ensure that locals are ready for them, perhaps through mullahs.

US officials raised the prospect of local men being offended by the sight of Western men kayaking down the river as women collect water from the banks. Potential investors who spoke at a recent Panjshir tourism conference organised by the US-led Provincial Reconstruction Team also raised practical concerns such as Afghanistan’s lack of long-term leases for hoteliers.

Provincial leaders, though, are hungry for the revenue which tourism could bring.

“Tourists are not coming here to take things from us or insult our religion but to breathe the fresh air in the province,” Abdul Rahman Kabiri, deputy governor of Panjshir, told the conference.

“Tourists will play an important part in the development of this country.” Panjshir will be among the first wave of places in Afghanistan to pass from foreign to local security control from July.

US officials hope that, as their mission here winds down, industries such as tourism can grow enough to help make up for a likely shrinkage of funding from their government and other sources in future.

However, they acknowledge that the success or failure of that idea turns on whether there is peace in Afghanistan after the international troop drawdown, or still more war.

Unama » Afghanistan Sees Surge in Domestic Tourist Industry

UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN AFGHANISTAN

July 5, 2009

By Tilak Pokharel

Afghanistan hasn’t seen a major influx of foreign tourists since the 1970s, but the budding tourism industry has in recent years seen a surge in Afghans visiting different parts of their own country, giving hope for tourism entrepreneurs.

Zaman-e-din Baha, the Director of the Afghan Tourist Organisation (ATO), says major tourist destinations like Badakshan, Bamyan, Kunduz, Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat have seen a growth in the number of domestic tourists since the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

“We are ready to provide good facilities to tourists,” says Baha, seated in his Kabul office that is decorated with posters of different Afghan tourist destinations. “There are 300 travel and tour agencies already established across the country with government approval.”

Baha rises from his chair and picks up postcards featuring different scenes of Afghanistan’s culture, traditions and landscapes. “TOURISTS!” is written on the reverse of each postcard. “You are the peace ambassadors and cultural messengers. Afghanistan welcomes you with five thousand years of ancient culture, spectacular views and historical areas. Come and visit Afghanistan,” the message concludes.

Though ATO’s appeals to foreign tourists haven’t yet materialised, Afghans like Daryamard are spending time and money visiting places across the country.

“I feel that it is a shame that Afghanistan has such fascinating natural sceneries that have not been enjoyed for the past 30 years,” says Daryamard, originally from northern Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan is definitely one of the most spectacular places [in the world] and I want Afghans to visit their country as I believe it contributes a great deal to the economy.”

Daryamard says he has visited Jalalabad, Dara-e Noor in Nangahar, Kunduz and most other northern parts of Afghanistan.

The ATO, part of the Afghan Ministry of Information and Culture, has local departments authorised to issue Afghan visas to foreign tourists in Kunduz, Herat, Jalalabad, Kandahar and Mazar.

Muqim Jamshady, the Chief Executive Officer of Afghan Logistics and Tours, a private tour agency, says it is mostly those who were born in Afghanistan before the war and those who have studied Afghanistan that are travelling across the country. He says only rich Afghans can afford to be tourists at the moment.

While ruing the adverse security conditions, Jamshady says, “Whatever happens in one part of the country, the whole country is affected and the tourists are deterred.”

However, he is optimistic about the future of the tourism industry in Afghanistan. “One day, peace will come,” says Jamshady, whose phones ring almost non-stop as he talks to UNAMA. “Tourism will be a major thing in the future. Major investment should be made in this sector.”

One of Afghanistan’s most respected historians and researchers, Nancy Dupree, says the first foreigners coming to Afghanistan in large numbers were “hippies on drugs,” followed by wealthier WTs or world travellers in the 1970s.

Dupree, 81, who has written five guidebooks on Afghanistan, as well as getting involved in other research since her arrival in the country in the early 1960s, says the WTs were looking for new adventures, while at the same time wanting good services – which was not possible at that time.

“When they [WTs] came here, I was trying to attract them in Afghanistan through the guidebooks,” says Dupree. “Otherwise, they would tell others not to go to Afghanistan because there are no trees, no roads etc.”

Dupree, who currently heads the Afghanistan Centre at Kabul University, says she doesn’t have time to write another guidebook although people keep asking her to do so. “Kabul was a very pretty city before the war started in the late 1970s.”

“There are still great potential for tours, particularly for those who like the outdoors, mountains, climbing,” says Dupree, who is particularly happy about the declaration of Afghanistan’s first national park in Bamyan two weeks ago.

https://unama.unmissions.org/afghanistan-sees-surge-domestic-tourist-industry

BBC News » Do tourists really go to Afghanistan?

British Broadcasting Corporation

Aug 4, 2016

By Roland Hughes

A Taliban attack on a group of foreign tourists in Afghanistan, that left at least six people wounded, is not the first of its kind in the country.

However, while civilian casualties in Afghanistan have reached their highest-recorded level, attacks on tourists are rare.

The fact Afghanistan attracts tourists at all may come as a surprise to some, but a number of companies offer tours to the country where there were more than 11,000 casualties of violence last year.

The UN World Tourism Organization does not receive statistics from the Afghan government on tourist numbers, so it is difficult to track how many visitors are making it there.

Those figures show a big drop in the amount of money spent by tourists in the country – from $168m (£128m) in 2012 to $91m in 2014, the most recent year’s statistics available.

Muqim Jamshady is chief executive of Kabul-based Afghan Logistics And Tours, which helps organise trips and treks for visitors in safe parts of the country.

He told the BBC that up to 300 tourists used their services in 2003, but the number had now dropped to about 100 a year.

The fall in visitors has come as deaths from violence in Afghanistan have increased.

The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) advises against travelling to most parts of Afghanistan, adding that “there is a high threat from terrorism and specific methods of attack are evolving and increasing in sophistication”.

The US State Department goes even further, warning there is a risk of “kidnapping, hostage taking, military combat operations, landmines, banditry, armed rivalry between political and tribal groups, militant attacks, direct and indirect fire, suicide bombings, and insurgent attacks, including attacks using vehicle-borne or other improvised explosive devices”.

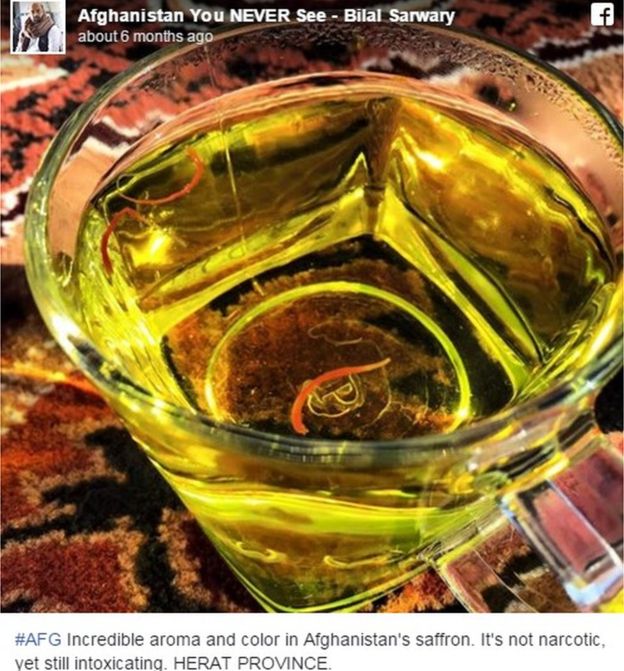

Huge areas of Afghanistan are no-go areas for visitors, said Bilal Sarwary, an Afghan journalist who does his part to promote the ‘Afghanistan You Never See’ on his Facebook page, but that is not to say everywhere is inaccessible.

“The State Department, the FCO, all advise it is not safe. It is not Sri Lanka or the Maldives, but it’s not Libya or Syria either,” he said.

“There are places in Afghanistan that are totally safe for tourists. If you fly into Kabul, then fly to Bamiyan or Herat, that’s the safe way.

“What attracts people to Afghanistan is its diverse landscape – from mountains to deserts to lakes.”

In pictures: Bamiyan valley

If you are visiting Afghanistan, Bilal’s advice is to carry out plenty of research and avoid roads by flying to your destination.

“Most people I know who’ve been as tourists had a friend or family member who was an aid worker,” he said. “It’s not totally impossible.”

The attack on the tourists, who were travelling with security forces, happened on a road between Ghor and Herat in the west of the country.

While Herat itself is seen as relatively safe, Bilal expressed his surprise that tourists were travelling on that particular road.

The BBC’s chief international correspondent, Lyse Doucet, who has been travelling to Afghanistan since 1988, said: “There are areas unaffected by the Taliban where you can enjoy Afghans’ hospitality, kindness and gentleness, see beautiful sights and stay in decent hotels.”

The risk, Lyse said, was not necessarily being in any one place, but in travelling between safe places.

“You can’t say that any whole country is unsafe,” she said. “But that’s where local knowledge comes in.

“Even if you are going on a trip to Italy, you get the best advice – well you have to ask the same questions in Afghanistan, but you need to ask them in a much more comprehensive way to make sure the sources of your knowledge are good.”

The attack comes at a time when Herat, a city once occupied by Alexander the Great in 330BC, is seeking to capitalise on its relatively safe image to bring in more tourists.

“It’s a country that’s so cut off from the rest of the world when it comes to trade and tourism,” Lyse said.

“So for those Afghans who want to see a better future, it’s really depressing and demoralising, because every time they take a step up, they have to take a step back down.”

Muqim Jamshady, of Afghan Logistics and Tours, is one of those taking another step back. “I’m really sad,” he said. “And angry.”

Afghan News » Afghan team’s journey to ‘Incredible India’

Afghan team’s journey to ‘Incredible India’

February, 2007

By India Review

Lemonde Diplomatique » Afghan Tours

Lemonde Dimplomatique

November, 2008

By Don Duncan

Muqim Jamshady, 28, realised there were advantages to speaking English when he started to earn more money than he had ever dreamed of, translating for US and coalition forces and as a local aide for international press organisations in Afghanistan covering the fall of the Taliban.

Within a year of their fall, in 2001, he had established Afghan Logistics and Tours, now the leading tourism company and provider of translation to foreign press, armed and diplomatic services. The company is still more a logistics provider than a tour operator ; Jamshady says tourism represents about 10% of his businesses. “But we hope to increase our tourism to 60-70% once Afghanistan gets more peaceful.” He doesn’t want to speculate when that may be.

He has a fleet of cars and a troop of interpreters and drivers in Kabul, and a network of guides across Afghanistan in Mazar-i-Sharif, Herat and Faizabad. All have worked primarily as fixers who translate and facilitate stories for journalists, and they are well connected in their cities. A meeting with the governor of the province or an afternoon with rug-makers in the mountains are just a phone call away.

Afghan Dreams » Afghan Dreams

dougmckinlay.com

By Doug McKinlay

Search any news channel, open any newspaper and there will be an instant picture of southern Afghanistan. The conflict, as well as the terrain, is now as familiar to us as our own backyard. But to judge a whole country based on such a limited image doesn’t do it justice. While war rages in the south, even affecting Kabul, the capital, most northern provinces are experiencing relative calm. Afghanistan is truly a divided country.

It is into this schizophrenic environment that I set out. My goal: to gain an understanding of what Afghanistan is all about and to investigate the contrast between north and south, a difference so acute that even small, but hardcore groups of tourists are being encouraged to return to the north.

“We are tired of war,” said Muqim Jamshady, the 27 year-old Manager of Afghan Logistics and Tours. “I even hate the word war. We just want to get on with business and show people from other parts of the world that Afghanistan is more than just fighting.”

As if to emphasize this, he tells me of some recent visitors: “Most of the tourists we’re getting, especially in the past couple of years, are from Britain and the United States. Our last group was American. Fifteen people from all over the US, the youngest was 75 and the oldest 91.

Still, the greatest danger to visitors is the indiscriminate and unpredictable nature of the violence. This makes any visit to the south, where the Taliban are staging an unexpected comeback, out of the question. Even in Kabul, despite being NATO’s stronghold, fresh violence is on the rise. However it’s not the same in other northern cities.

The western city of Herat is arguably the most normal city in the country at the moment, in terms of relative safety. Local people are going about their business as if the conflict in the south isn’t happening, getting out at night on foot – unheard of in Kabul – is not a problem and many of the sites of interest are open. The Citadel, first built by Alexander the Great, has been a fortress to many passing empires, and is now open to the public for the first time in a generation. The centre of Herat’s religious life is the 800 year-old Friday Mosque. It is captivating in the muted early morning light, while the remains of the 15th century minarets of the Mousallah Complex glow orange in the late afternoon sun.

Mazar-i-Sharif lies 320 kilometres north of Kabul along one of the country’s only sealed roads in the Province of Balkh. It has been dubbed the ‘linchpin’ city in the War on Terror. As such, it has become an important staging area for NATO forces in Afghanistan. The collateral affect has made Mazar-i-Sharif secure. The city’s main draw is the fabulous Blue Mosque, which houses the Tomb of Hazrat Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammad. It is therefore an important site to Muslims from all over the world.

The calm the north enjoys is in stark comparison to the troubles in the south, a product of a fundamental rift that splits this country down the middle. It is partially religious but primarily economic. The north has better land, more water, oil and access to employment and education, while the south is mired in an opium poppy economy that ultimately is only profitable for the few warlords who control the trade; and increasingly to the Taliban who are now allying with poppy growers in order to raise money. It’s these differences that the Taliban are now exploiting.

“The Taliban want to live in a vacuum,” said Muqim. “They want to turn the clock back to the 14th century. Most of the suicide bombers aren’t even from Afghanistan. This fight is not between the Afghani people and the West. It’s between Jihadis from Pakistan, Azerbaijan and Chechnya who come here because they want to fight the Americans and their allies.”

During the past few weeks the situation in the south has become so delicate that NATO chiefs are calling on alliance partners to enlist more of their troops for the fight. However, as tenuous as the south is Muquim insists that the Taliban will never take Kabul again, that too many people would resist. As if to stress the point, there is a palpable buzz about the city. Notwithstanding an increase in Kabul-based suicide bombers business is thriving.

After the initial ousting of the Taliban in 2001, there were high hopes that Kabul, and the country as a whole, would begin to normalise. Into this environment stepped a multitude of foreign government and non-government organisations (NGO), all with their own ideas of how Afghanistan should proceed and all with many millions of dollars to help make it happen.

Within a short time however, the Afghan government went on record criticising the efficacy of many of the NGOs operating in Afghanistan. Much of that criticism was aimed at how international donor money was distributed and at the pace of reconstruction. How accurate the government’s criticisms are is anybody’s guess. But not all NGOs are created equal.

The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) is the umbrella organisation founded by His Highness the Aga Khan to promote and develop a number of initiatives in the areas of culture, health, education and economic development, part of which is the promotion of tourism.

As such the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development invested US$36.5 to refurbish and rebuild an existing hotel in Kabul, bringing it up to international five-star standards. The Serena Hotel is the only true five-star in Kabul to date.

It opened in November 2005; its 177-room capacity is housed in a squat three-storey u-shaped structure surrounded by high security walls. Coloured much the same as the surrounding hills it blends in with the natural earth tones of Kabul. Once past the heavily armed main gate the interior courtyards are quiet and peaceful, offering a nice break from Kabul’s busy roads. The rooms are well appointed and would meet the standards of any Western luxury hotel.

Still, the question remains: Why a five-star hotel in one of the most unpredictable cities in the world?

“Part of the reason why the hotel was built was to help develop the local economy and help change the image of Afghanistan,” said Chris Newbury, the Serena’s general manager. “We provide jobs for local people. We train them in the industry and even if they leave us to start their own hotel or guesthouse hopefully the training they receive here will help improve the country’s overall hotel industry.”

The Serena is not the only project the AKDN is involved with in Afghanistan. It is the principle backer of the telecommunications company Roshan, which provides affordable mobile telephone and Internet service to people all over the country. In addition, they also provide funding for cultural programs that are currently working to restore many of Kabul’s historic buildings and sites. Principally the Babur Gardens, Kabul’s Old Town, and the Tamir Shah Mausoleum.

Hotels aside, I was more interested in Kabul itself and the surrounding country.

No one could call Kabul a pretty city, at least not in a conventional way. It sits in a valley among dun-coloured hills, one-story mud-brick houses sweeping up their slopes camouflaged into the background. In the city, the traffic is thick, congested almost to a standstill. The architecture is a mix of slapped together one or two storey buildings, 1970’s low-rises and post-Taliban steel and glass structures that look as if they have been lifted from the streets of Shanghai. Still, there is an energy here; after more than two decades of war the city is alive again.

Along Chicken and Flower Streets, the one-time epicentre of 1970s hippy culture, shops are open and flourishing. The markets are buzzing, walking among the busy stalls is like strolling through the pages of a National Geographic magazine. Restaurants and guesthouses are opening at a pace not seen since before the Russian invasion in 1979. And there are taxis, so many taxis.

Travelling overland beyond Kabul involves its own set of difficulties. Although independent travel is possible, it’s not recommended. Public buses do exist, but are so unreliable with notoriously unpredictable departure times they are all but useless. Hire cars are available, however it would take a very knowledgeable and skilled driver to negotiate the dusty tracks that are Afghanistan’s roads. Even air transport is a bit of a crapshoot. Ariana Afghan Airlines, the national carrier, is known for either delaying its domestic flights for anything up to 24 hours or completely cancelling flights without warning. However, getting out of Kabul is not impossible.

The best option is to employ an organisation like Afghan Logistics. With a small fleet of 4X4 vehicles, and more importantly knowledge and experience of the country, they are able to meet most tourists’ travel needs. I used such a service for a visit to the Bamiyan Valley, site of the famous standing Buddhas destroyed by the Taliban in March of 2001.

It was an eight-hour journey along an impossibly pitted and potholed unsealed road. But it was worth every bump, every knock and every grain of sand gritted between my teeth. This is part of the Silk Route and the scenery is overwhelming. Bone dry hills, ranging in hue from desert grey to deep red contrast with a lush green belt of orchards and fields of wheat next to the narrow waters of the Bamiyan River.

The Buddhas themselves, although destroyed, are still powerful. I arrived in time to catch the last rays of the afternoon sun lighting up the cavernous niches that were once their home. From my perch high above the valley it is all so serene, farmers tend their fields, children play as they return home from school and women herd goats along dusty roads. Yet just a few hundred kilometres south a war rages on, it doesn’t seem possible.

In the end it is easy to depict northern Afghanistan as much safer than the south. But it is all relative. Saying that the northern provinces are free from danger would be misleading. After 25 years of war there is little experience of peace among today’s Afghanis. And as one British aid worker told me: “Afghanistan is safe, then it isn’t.” It’s that quick and it knows no boundaries. But if the right precautions are taken, the correct research done and a reliable travel company used then a trip to Afghanistan can be a rewarding and exhilarating experience.